Extend the Engine

You can write plug-ins that add new features to the runtime interactive engine, expose new objects and functions in the Lua gameplay API, integrate with external middleware SDKs or other libraries, etc. You could even write your gameplay code entirely in C rather than using Flow and Lua, if you are comfortable doing so.

This section provides some tips on getting started extending the engine with your own plug-ins.

The most important resource for working on engine plug-ins is the repository of example plug-ins. If you don't already have these examples, see Example Plug-ins.

Start by looking at the samples/simple_plugin example. It's a very minimal plug-in that shows the basic skeleton of an interaction between the engine and a plug-in, like the one described in the following sections.

Then move on to the samples/bigger_plugin, which shows how you can create a new resource type, define how that resource gets compiled into runtime data, and set up Lua functions for the project to access the data in that resource at runtime.

We really recommend basing your plug-in on the stingray-plugin repository. It's already set up with everything you'll need to compile your code to a .dll using Visual Studio 2015, which will make it way easier for you to get started.

You'll need the SDK header files. You can find them under stingray_sdk in the example repository, or under plugin_sdk in your 3ds Max Interactive installation folder. (If you use the stingray-plugin repository repo, it'll fetch these headers for you automatically so you won't have to worry about it.)

The reference documentation contains a browsable companion to the APIs defined in the SDK header files.

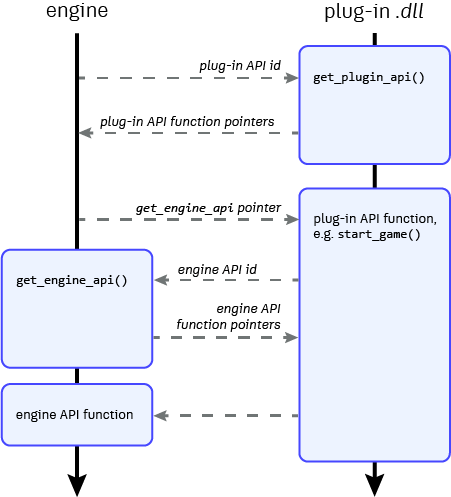

The engine's plug-in interface is based around a consistent pattern of interactions between the engine and the plug-in. All of these interactions are based on a shared set of API definitions. Each side queries the other to retrieve the APIs that the other side supports:

The engine first queries the plug-in for its API by calling a predetermined get_plugin_api function. The plug-in provides the engine with a struct that contains pointers to whatever functions the plug-in implements from their shared plug-in API definition.

When the engine calls those functions defined by the plug-in, it passes along a get_engine_api function pointer of its own. The plug-in can call that function to query the engine in return, in order to retrieve APIs that expose engine services to the plug-in. The plug-in can then call functions in those returned APIs in order to make the engine perform the tasks it needs.

The following image summarizes this workflow:

These are the basic steps for getting a plug-in to integrate with the runtime engine. All of the example plug-ins do these things, so look in their code for illustrations.

Include the plugin_api.h file.

#include "engine_plugin_api/plugin_api.h"

When the engine and the plug-in call each other as shown in the diagram above, they use a shared set of IDs to identify the APIs that they are requesting. Each ID always corresponds to a particular struct, defined in the plugin_api.h file. So both the engine and the plug-in need to include this file in order to make sure that the identifiers and API definitions match.

Define a function with the following signature:

__declspec(dllexport) void *get_plugin_api(unsigned api_id)

The plug-in interface uses C rather than C++, to avoid ABI incompatibilities between different versions of C++ and different compilers. If you want to compile your plug-in using C++, you can wrap your get_plugin_api function in an extern C block, like this:

extern "C" { __declspec(dllexport) void *get_plugin_api(unsigned api) { ... } }This avoids the function name becoming mangled in the compiled .dll.

Each time the engine calls your plug-in's get_plugin_api function, it passes a PluginApiId that identifies an interface it wants your plug-in to provide. If you want your plug-in to support the requested interface, your implementation of get_plugin_api should respond by creating a new instance of the struct that matches that requested API. For each function in that interface that you want your plug-in to support, you should set the pointer for that function in your instance to a function that you write in your plug-in. Once you've set up all the functions you want to support, return the struct.

The main plug-in API that you'll want to handle is identified by the PLUGIN_API_ID, which identifies the PluginApi struct. This example responds to the engine sending a PLUGIN_API_ID by setting up a PluginApi struct with a pointer to a custom implementation for the setup_game() function:

__declspec(dllexport) void *get_plugin_api(unsigned api_id) { if (api_id == PLUGIN_API_ID) { static struct PluginApi api = {0}; api.setup_game = setup_game; return &api; } return 0; }The engine converts the returned pointer into a pointer to the corresponding PluginApi struct. It then uses that struct to call the functions you've defined.

There are some other plug-in APIs that the engine requests (the RENDER_CALLBACKS_PLUGIN_API_ID for example), and we may add more in future.

So far, you've set up the engine to call out to your plug-in at specific moments in its lifespan. But usually, you'll want the interaction to go both ways: you'll want your plug-in code to call out to the engine in order to ask the engine to do something for you -- to load a world, spawn a unit, compile a resource, render some data, etc.

The typical pattern is for your plug-in to call a get_engine_api function provided by the engine in order to request any service APIs it needs from the engine. In each call, you pass a value from the PluginApiId enumeration to tell the engine which interface you want. Then, your plug-in can cache the returned struct in a variable, and use it anytime to carry out operations in the engine.

For example, the simple plug-in uses this implementation of the setup_game function to request the LuaApi interface from the engine. It can then use any of the functions defined in that interface to interact with the engine's Lua environment -- in this case, exposing a new function that could be called by a project's Lua scripts as stingray.SimplePlugin.test().

struct LuaApi *_lua; static void setup_game(GetApiFunction get_engine_api) { _lua = get_engine_api(LUA_API_ID); _lua->add_module_function("SimplePlugin", "test", test); }

Compile your plug-in to a .dll file.

This can be tricky if you're not used to developing in C. We really recommend starting from the example plug-ins, which are all set up with their own Visual Studio projects.

You must target the x64 platform. Also, dynamically linked plug-ins are currently supported only on Windows; see Alpha SDK Limitations.

Get the engine to load your .dll. See Loading the plug-in DLL below.

Once you have this basic level of integration set up between the engine and your plug-in, you can take it farther by exploring what other functions you can implement from the main PluginApi interface, and what other service APIs the engine provides for plug-ins. See Useful engine plug-in interfaces.

The easiest way to get the engine to load your plug-in .dll automatically is to set up a runtime_libraries extension in your .stingray_plugin description file. While your plug-in is loaded in the editor, any engine instances that you launch through the editor (using Test Level or Run Project) will automatically load the corresponding config of your plug-in.

NOTE: The runtime_libraries extension does not yet package your .dll files into deployed standalone builds that you create through the Deployer panel. When you deploy, you'll still have to manually copy your .dll file to the plugins directory within the build output folder, or add your plug-in to a manifest file that identifies files that need to be copied automatically during deployment. See Distribute and Install a Plug-in for more details.

This extension accepts the following parameters:

runtime_libraries = [

{

name = "my_engine_plugin"

paths = {

win32 = {

dev = "binaries/engine/win64/dev/my_engine_plugin_w64_dev.dll"

debug = "binaries/engine/win64/debug/my_engine_plugin_w64_debug.dll"

release = "binaries/engine/win64/release/my_engine_plugin_w64_release.dll"

}

}

}

name

A descriptive name that identifies this set of libraries. This name should match the name that your plug-in returns in its implementation of PluginApi::get_name().

paths

Provides the paths to your libraries for each target platform and each different engine build configuration that it supports. When the editor starts an engine on a target platform that matches one of the keys in this list, and that engine's build configuration matches one of the keys set for that platform, the editor configures the engine to load the .dll file that corresponds to that configuration.

If your plug-in needs to load multiple .dll files for some reason, you can include multiple objects in the runtime_libraries list.

On platforms that support dynamic plug-ins (currently Windows only), the engine keeps a list of folders that it checks at startup for .dll files. Your plug-in .dll has to be in one of these folders in order for the engine to load it automatically.

By default, the list of plug-in folders contains only the plugins folder under the engine executable. You can simply copy your plug-in's .dll file to this location.

You can add paths to this list by passing the --plugin-dir <folder> command-line parameter when you start the engine. See the Engine command-line reference.

You can load (and unload) plug-ins dynamically from other paths at runtime:

In Lua, use the functions in the stingray.PluginManager API, such as PluginManager.load_plugin() and PluginManager.load_relative_plugin().

In C/C++, if you have a loaded plug-in that needs to load another plug-in dynamically, use PluginManagerApi::load_relative_plugin().