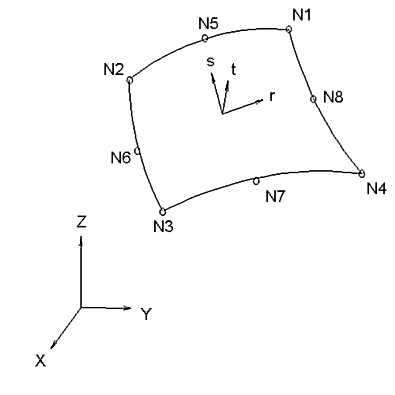

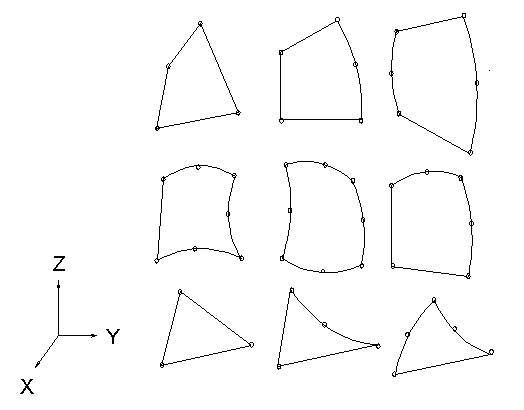

Shell elements are 4- to 8-node isoparametric quadrilaterals or 3- to 6-node triangular elements in any 3D orientation. The 4-node elements require a much finer mesh than the 8-node elements to give convergent displacements and stresses in models involving out-of-plane bending. Figure 1 shows some typical shell elements.

The General and Co-rotational shell element is formulated based on works by Ahmad, Iron and Zienkiewicz and later refined by Bathe and Balourchi. It can be applied to model both thick and thin shell problems. Also, the geometry of a doubly curved shell with variable thickness can be accurately described using this shell element.

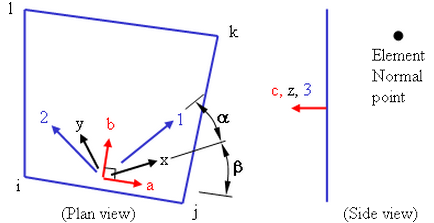

Figure 1: Sample 3D Shell Element

Figure 2: Typical Shell Elements

The Thin shell element is based on thin plate theory. The bending behavior of the element is based on a discrete Kirchoff approach to plate bending using Batoz's interpolation functions. This formulation satisfies the Kirchoff constraints along the boundary and provides linear variation of curvature through the element. The membrane behavior of the element is based on the Allman triangle which is derived from the Linear Strain Triangular (LST) element. A general curved surface is approximated by this element as a set of facets formed by the planes defined by the three nodes of each element. For these reasons a well-refined mesh is necessary.

The element geometry is described by the nodal point coordinates. Each shell element node has 5 degrees of freedom (DOF) - three translations and two rotations. The translational DOF are in the global Cartesian coordinate system. The rotations are about two orthogonal axes on the shell surface defined at each node. The rotational boundary condition restraints and applied moments also refer to this nodal rotational system. The two rotational axes (V1 and V2) are usually automatically determined by the processor and you do not have to specifically orient them.

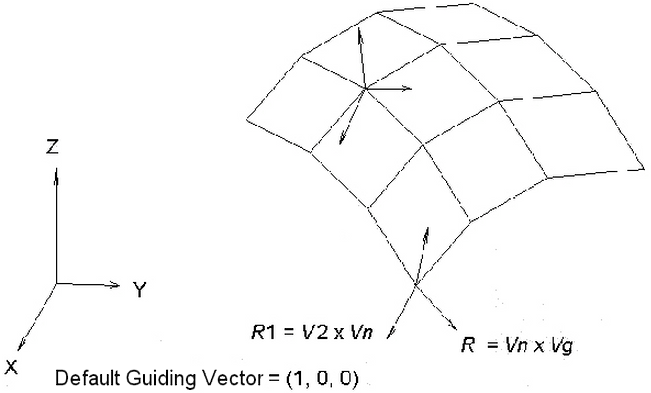

The rotational R1 and R2 directions at each node are determined by the cross product of the normal vector Vn and a guiding vector Vg as follows. See Figure 3 (V1 and V2 are the unit vectors along the R1 and R2 rotational direction, respectively):

R1 = V2 x Vn

R2 = Vn x Vg

The default guiding vector Vg is (1,0,0). In other words, the R1 axis is actually the projection of the guiding vector Vg onto the shell surface, and the R2 axis lies on this shell surface but orthogonal to R1 and the normal vector Vn. Figure 3 shows the orientation of R1 and R2 using the default guiding vector (1,0,0).

You can enter two guiding vectors for each shell element part. If the guiding vector has zero projection onto the shell plane, the second guiding vector is used. You can also specify a guiding vector for a specific node.

The processor determines the normal direction of each shell element node by taking the average of different normal vectors from different elements connecting to the node point. The element normals are computed from the element corner nodes data. From this normal vector, two rotational axes are then determined. You can also specify the normal vector direction directly and suppress the processor's calculations. The two rotational vectors can also be oriented in a user-specified direction such that skewed rotational restraints or moments in 3D space can be easily defined.

When multiple shell panels intersect at an area (usually at a line of intersection), it is difficult to specify the rotational DOF at the area. In this case, the nodes at the intersecting area should be designated as 6-DOF nodes.

Figure 3: The Rotational Degrees of Freedom Determined Using Vg

Six DOF nodes will have globally oriented rotational DOF instead of the unique R1 and R2 DOF at each node.

Three-dimensional shell elements are Type 26 elements and are 4- to 8-node isoparametric quadrilaterals or 3- to 6-node triangular elements in any 3D orientation. They can be applied to models for both thick and thin shell problems. Also, the geometry of a doubly curved shell with variable thickness can be accurately described using this shell element. Theoretical aspects of this element formulation can be found in Bathe and Balourchi.

The element geometry is described by the nodal point coordinates. Each shell element node has five degrees of freedom (DOF) - three translations and two rotations. The shell elements' rotational DOF are defined by the shell guiding vectors. The projection of the guiding vector, Vg, onto the shell element will be the first rotational axis (R1). The second rotational axis is orthogonal to both the R1 and the shell normal vector (Vn), using the rule R2 = Vn x Vg. The default guiding vector is (1, 0, 0). If the guiding vector is parallel to the shell normal vector, Vn, a second guiding vector [(0, 1, 0) by default] will be used to define the R1 direction.

Shell Element Parameters

There are three types of shell elements available that provide different options. The difference between these types is explained in the previous section. The shell element type can be selected in the Element Formulation drop-down box, found on the Advanced tab of the Element Definition screen. However, the default selection based on the material model is usually acceptable.

First, you must specify the material model for this part in the Material Model drop-down box, on the General tab. The available shell material models are:

- Isotropic: This material model option is used for parts that will only experience deflections in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve. To use this material model, the parts must have identical material properties in all directions. A single modulus of elasticity and Poisson's ration will be the requested material properties. Available for General, Co-rotational and Thin shell elements.

- Orthotropic: This material model option is used for parts that will only experience deflections in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve. The part may have different material properties in certain directions. Specifically, the material properties may be different in one or more of the three orthogonal directions in a rectangular coordinate system. This option is available for General, Co-rotational and Thin shell elements. See the paragraph Controlling the Orientation of Shell Elements below for details on setting up the material axes.

- von Mises with Isotropic Hardening: This material model option is used for parts that may experience plastic deformation during the analysis. A bilinear curve will be defined to control the stress-strain relationship. This option will only be available for General and Thin shell elements.

- von Mises with Kinematic Hardening: This material model option is also used for parts that may experience plastic deformation during the analysis. A bilinear curve will be defined to control the stress-strain relationship. This material model option is preferred over the von Mises with isotropic hardening material model option if the model will undergo cyclical loading (Bauschinger effect). This option will only be available for General and Thin shell elements.

- von Mises Curve with Isotropic Hardening: This material model option is used for parts that may experience plastic deformation during the analysis. You will be able to specify a stress-strain curve with multiple data points to control the stress-strain relationship. This option will only be available for General and Thin shell elements.

- von Mises Curve with Kinematic Hardening: This material model option is used for parts that may experience plastic deformation during the analysis. You will be able to specify a stress-strain curve with multiple data points to control the stress-strain relationship. This material model option is preferred over the von Mises with isotropic hardening material model option if the model will undergo cyclical loading (Bauschinger effect). This option will only be available for General and Thin shell elements.

- Mooney-Rivlin: This material model is used to model hyperelastic materials such as rubber. This option will only be available for General shell elements.

- Ogden: This material model is used to model hyperelastic materials such as rubber. This option will only be available for General shell elements.

- Viscoelastic Ogden: A viscoelastic variation of the Ogden (hyperelastic) material model. This option will only be available for General shell elements.

- Viscoelastic Mooney-Rivlin: A viscoelastic variation of the Mooney-Rivlin (hyperelastic) material model. This option will only be available for General shell elements.

- Composite: This material model is used to model composite materials in which multiple laminae affect the material properties. The material must remain in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve during the analysis and the material properties must be identical at all temperatures. You will be requested to define the material properties and failure criteria for each layer of the composite in the Composite tab. This option will only be available for Co-rotational shell elements. See the paragraph Controlling the Orientation of Shell Elements below for details on setting up the material axes.

- Temperature Dependent Composite: This material model is used to model composite materials in which multiple laminae affect the material properties. The material must remain in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve during the analysis and the material properties may vary with temperature. You will be requested to define the material properties and failure criteria for each layer of the composite in the Composite tab. This option will only be available for Co-rotational shell elements. See the paragraph Controlling the Orientation of Shell Elements below for details on setting up the material axes.

- Thermoelastic: This material model is used to model materials what will only experience deflections in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve but may also experience stress due to a temperature difference. This option is available for General, Co-rotational and Thin shell elements.

- Temperature Dependent Orthotropic: This material model is used for parts that have different material properties in certain directions that also vary with the temperature. Specifically, the material properties may be different in one or more of the three orthogonal directions in a rectangular coordinate system. The material properties will be specified at multiple temperatures. The values will be linearly interpolated between temperature values. The temperature range for which the material properties are defined must include the expected temperatures. This option is available for General, Co-rotational and Thin shell elements. See the paragraph Controlling the Orientation of Shell Elements below for details on setting up the material axes.

Specify the thickness of the shell elements in the Thickness field. The element is considered to be drawn at the midplane of the shell element. You must enter a value for the thickness to run the analysis. If the Composite option is selected in the Material Model drop-down box, this field will not be available. In this case, the sum of the thicknesses of the laminae defined in the Composite tab will be displayed in this field.

For the shell elements in this part to have the midside nodes activated, select the Included option in the Midside Nodes drop-down box. If this option is selected, the shell elements will have additional nodes defined at the midpoints of each edge. (For meshes of CAD solid models, the midside nodes follow the original curvature of the CAD surface, depending on the option selected before creating the mesh. For hand-built models and CAD model meshes that are altered, the midside node is located at the midpoint between the corner nodes.) This will change a 4-node shell element into an 8-node shell element. An element with midside nodes will result in more accurately calculated gradients. Elements with midside nodes increase processing time. If the mesh is sufficiently small, then midside nodes may not provide any significant increase in accuracy.

Use the Analysis Type drop-down to set the type of displacement that is expected. Small Displacement is appropriate for parts that experience no motion and only small strains and will ignore nonlinear geometric effects that result from large deformation. Large Displacement is appropriate for parts that experience motion and/or large strains. (Depending on the type of shell element chosen, there may be other options on the Analysis Formulation on the Advanced tab that are affected by the Analysis Type drop-down.)

- The displacement at midside nodes are always output. The stress and strain at midside nodes are output only if the user activates the option to output these results before running the analysis. The option is located under the Setup

Model Setup

Model Setup  Parameters

Parameters  Advanced dialog on the Output tab. (See the page Setting Up and Performing the Analysis: Nonlinear: Analysis Parameters: Advanced Settings: Control Output Files for details.)

Advanced dialog on the Output tab. (See the page Setting Up and Performing the Analysis: Nonlinear: Analysis Parameters: Advanced Settings: Control Output Files for details.) - Use the

Options

Options  Analysis tab and set the Use large displacement as default for nonlinear analyses option to control whether the Analysis Type defaults to small or large displacement.

Analysis tab and set the Use large displacement as default for nonlinear analyses option to control whether the Analysis Type defaults to small or large displacement.

Composite Material Model

If the shell elements are using a composite material model, you can select a failure criteria using the Failure Criterion drop-down box in the Composite tab of the Element Definition dialog box. The available options and the corresponding equations used are:

- Tsai-Wu: If this option is selected, the Tsai-Wu (or quadratic tensor polynomial) criteria will be used to determine if the part fails the structural analysis. This criteria, considering the interaction between stresses in two directions, for an orthotropic layer under plane stress condition, is determined by the equation:

|

|

[1] |

where

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Xt = Axial or longitudinal strength in tension (>0)

Xc = Axial or longitudinal strength in compression (>0)

Yt = Transverse strength in tension (>0)

Yc = Transverse strength in compression (>0)

S = Shear strength

F12 = the stress interaction value entered in the material properties. If the value is 0, it will default to![]()

σ1 = Stress in principal material 1- direction

σ2 = Stress in principal material 2- direction

τ12 = Shear stress in principal material 1-2 plane

If equation [1] is not satisfied, the material has failed.

|

|

[2] |

where R is the strength/stress ratio.

Since each combination of stress components in [1] reaches its maximum when the left-hand side reaches unity, [2] can be substituted into [1] and yield:

![]()

Solving this equation for R yields:

where:

![]()

with the signs of the stresses σ ij reversed.

- Maximum Stress: If this option is selected, the maximum stress criteria will be used to determine if the part fails the structural analysis. The criteria is given as:

|

[3] |

where

σ1 = Calculated stress in 1 direction

σ2 = Calculated stress in 2 direction

τ12 = Calculated shear stress

Xc = Allowable compressive stress in 1 direction (>0)

Yc = Allowable compressive stress in 2 direction (>0)

Xt = Allowable tensile stress in 1 direction (>0)

Yt = Allowable tensile stress in 2 direction (>0)

S = Allowable shear stress (>0)

If the three conditions of equation [3] are not satisfied, the material has failed.

- Maximum Strain: If this option is selected, the maximum strain criteria will be used to determine if the part fails the structural analysis. The criteria is given as:

|

[4] |

where

ε1 = Calculated strain in 1 direction

ε2 = Calculated strain in 2 direction

γ = Calculated shear strain

T1c = Allowable compressive strain in 1 direction (>0)

T2c = Allowable compressive strain in 2 direction (>0)

T1t = Allowable tensile strain in 1 direction (>0)

T2t = Allowable tensile strain in 2 direction (>0)

S = Allowable shear strain (>0)

If the conditions of equation [4] are not satisfied, the material has failed.

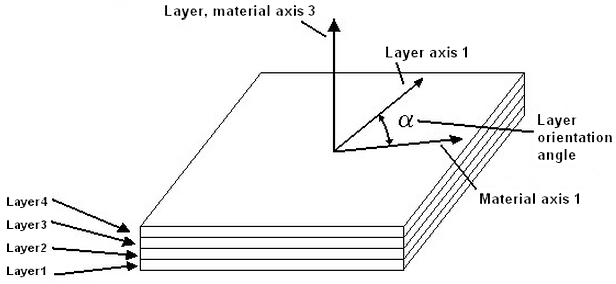

The Composite Laminate Stacking Sequence table can be used to define the layers of the composite. Layers are oriented and ordered as described below in Controlling the Orientation of Shell Elements. The Thickness column must be defined for each layer. The Orientation Angle column gives the angle α between the material axes (defined on the Orientation tab) and the fiber or layer axes. The material properties are entered according to the layer axes. To define the material properties for a layer, click in the Material column. A dialog will appear that will allow to select an existing material or Add a new material. (Also see the page Setting Up and Performing the Analysis: Nonlinear: Material Properties: Composite Material Properties for details.)

Define Thermal Properties of Shell Elements

If a shell element part is using a thermoelastic or temperature-dependent material model, you must specify a value in the Stress free reference temperature field in the Thermal tab of the Element Definition dialog. This value is used as the reference temperature to calculate element-based loads associated with constraint of thermal growth using bilinear interpolation of the nodal temperatures.

Control Orientation of Shell Elements

There are two types of axes that the user can control. One type is the axis normal to the shell elements. The main reason to specify the normal direction is for applying pressure to the element or specifying surface-to-surface contact. For composites, the normal direction controls which side of the element layer 1 is on. The second type of axes is the element's in-plane axes. This is useful when working with an orthotropic material model or you desire to get results in the element coordinate system.

In addition to these two types, there are three axis systems which the user may need to set:

- The element axes.

- The material axes, which is used for orthotropic and composite material models.

- The laminate axes, which is used with composite material models.

Element Axes:

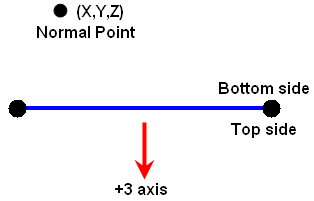

An element normal point is used to control the orientation of the element's normal axis (+3), or which side of the element is the top side (+3 side) and the bottom side (-3 side). The normal direction is determined by specifying a point in space using the X Coordinate, Y Coordinate, and Z Coordinate fields in the Element Normal section of the Orientation tab. See Figure 4. A positive normal pressure will be applied normal to the shell elements the direction of the +3 axis and thus will point away from the element normal point.

Figure 3: Determining the Element Normal

The edge-on view of the shell element is shown.

For a general FEA analysis, you can ignore the element's in-plane orientation, axes 1 and 2. The ability to orient element's in-plane axes is useful for elements with orthotropic material models and composite elements. The orientation of the 1 and 2 axes is done in the Orientation tab of the Element Definition dialog box.

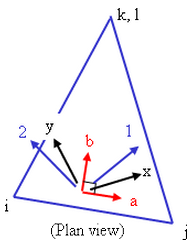

The Method drop-down box contains three options that can be used to specify which side of the element will be the ij side. The element axis 1 will be parallel to the ij side of the element. (Element axis 2 forms a right-hand system with axes 1 and 3.)

- If the Default option is selected, the side of an element with the highest surface number will be chosen as the ij side.

- If the Orient I Node option is selected, a coordinate must be defined in the X Coordinate, Y Coordinate, and Z Coordinate fields. The node on an element that is closest to this point will be designated as the i node. The j node will be the next node on the element following the right-hand rule about the element's normal axis (+3 axis).

- If the Orient IJ Side option is selected, a coordinate must be defined in the X Coordinate, Y Coordinate, and Z Coordinate fields in the Nodal Order section. The side of an element that is closest to this point will be designated as the ij side. The i and j nodes will be assigned so that the j node can be reached by following the right-hand rule about the element's normal axis (+3 axis) along the element from the i node.

Material Axis:

The material properties are entered in terms of the material axes for orthotropic materials, and the material axes can be defined from the element axes (or from a global reference) using the Material Axis Direction section of the Orientation tab on the Element Definition dialog. (Material properties for composite materials are entered in terms of the layer axes, as described below.)

In all cases, the material axis 3 will be perpendicular to element and in the same direction as the element axis 3.

If the enhanced shell elements are using an orthotropic or composite material model, the in-plane material axes 1 and 2 can be defined as follows:

- If the Element option is selected in the Method drop-down box, the material axes will be based off of the element local axes. Unless modified with the In-plane Rotation Angle, the material 1 and 2 axes will be parallel to the element 1 and 2 axes.

- If the Global X-axis option is selected, the projection of the global X axis onto the element creates the material axis 1.

- If the Global Y-axis option is selected, the projection of the global Y axis onto the element creates the material axis 1.

- If the Global Z-axis option is selected, the projection of the global Z axis onto the element creates the material axis 1.

- If the Point option is selected, a point will be defined in the X Coordinate, Y Coordinate, and Z Coordinate fields. The material axis 1 will be in the direction from the user-defined point to each integration or gauss point (and projected into the plane of the element). Essentially, this places axis 1 in a radial direction. Material axis 2 is in the plane of the element and forms a right-hand system with axes 1 and 3.

- If the Vector option is selected, a vector will be defined using the X Coordinate, Y Coordinate, and Z Coordinate fields. The material axis 1 is then parallel to the defined vector. Material axis 2 is in the plane of the element and forms a right-hand system with axes 1 and 3.

Regardless of the method used to orient the Co-rotational shell element material axes, you can use the In-Plane Rotation Angle field to rotate the material axes by a specified angle about axis 3. The rotations follow the right-hand rule about axis 3.

If the General shell elements are using an orthotropic material model, the in-plane material axes 1 and 2 can be oriented using two methods. The first method is to specify a vector parallel to material axis 1 by using the X Direction, Y Direction, and Z Direction fields. Material axis 2 is in the plane of the element and forms a right-hand system with axes 1 and 3. The second method is to define an angle in the Material Axis Rotation Angle field that will rotate material axis 1 about the element 3 axis using the right-hand rule (see Figure 5). This method will only be used if the values in the X Direction, Y Direction, and Z Direction fields are 0.

Figure 5: Rotation Angle Definition of Material Axis Direction

Layer Axes:

For composites, each layer of the laminate has a set of local axes. The layer 1-axis is the axis along the fiber of each individual layer. The layer 2-axis is the axis perpendicular to the fiber of each individual layer and in the plane of the element. The layer 3-axis is perpendicular to the element and therefore parallel to the local element axis c. (To avoid confusion between the layer axes and the element axes, the element axes are often referred to as a-b-c when working with composites, and axes 1-2-3 define the orientation of the fibers.) See Figures 6 and 7.

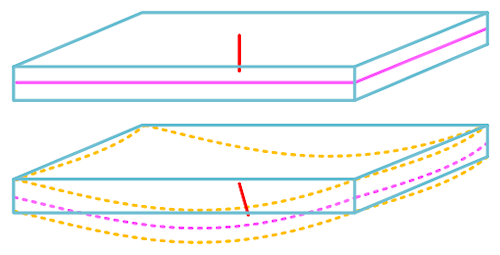

Figure 6: Laminae Stacking Order

The user enters the angle a for each layer using the Orientation Angle of the Composite Laminate Stacking Sequence table. Axis 3 is controlled by the element normal coordinate.

Figure 7: Alternate Depiction of Element, Material, and Layer Axes

The element axes a-b-c are based off of the element normal coordinate and the ij side of the element. The material axes x-y-z are rotated an angle b from the element axes. The element and material axes are the same for all layers in the stack. The layer or fiber axes 1-2-3 are rotated an angle β from the material axes and can be different angles for each lamina in the stack.

Advanced Shell Element Parameters

Select the formulation method that you want to use for the shell elements in the Analysis Formulation drop-down box in the Advanced tab.

- If the Material Nonlinear Only option is selected (General shell elements), nonlinear material model effects will be accounted for but all calculations will be performed based on the undeformed geometry. Thus, this formulation is suitable for parts with small strains and no motion.

- The Total Lagrangian option (General and Thin shell elements) will refer to the initial undeformed configuration of the model for all static and kinematic variables. This formulation is suitable for parts with motion and small strains. Note that the material properties should be in terms of engineering stress and strain.

- The Updated Lagrangian option (General shell elements) will refer to the last calculated configuration of the model for all static and kinematic variables. This formulation is suitable for parts with motion and large strain. Note that the material properties should be in terms of actual stress and strain.

- The Linear option (Co-rotational and Thin shell elements) will ignore nonlinear geometric effects that result from large deformation.

- The Geometrically nonlinear option (Co-rotational shell elements) will include nonlinear geometric effects that result from large deformation.

If the Allow for overlapping elements check box is activated, overlapping elements will be allowed to be created when the lines are decoded into elements. Overlapping may be necessary when modeling elements. This is especially true for problems confined to planar motion.

For the stress results for each element to be written to the text log file at each time step during the analysis, activate the Detailed stress output check box. This may result in large amounts of output.

If one of the von Mises material models has been selected, you can choose to have the current material state (elastic or plastic), current yield stress limit, current equivalent stress limit and equivalent plastic strain output at corner nodes and/or integration points at every time step. This is done by selecting the appropriate option in the Additional output drop-down box.

If you are using General shell elements, select the integration order that will be used in this part in the Integration Order drop-down box. For rectangular shaped elements, select the 2nd Order option. For moderately distorted elements, select the 3rd Order option. For extremely distorted elements, select the 4th Order option. The computation time for element stiffness formulation increases as the third power of the integration order. Consequently, the lowest integration order which produces acceptable results should be used to reduce processing time.

The reduced integration scheme can be used to improve the shear locking behavior for curved shell configurations by activating the Reduced integration for membrane shear terms or Reduced integration for transverse shear terms check box. If the thickness of the shell elements is less than 1/10 of the length or height, reduced integration is recommended. If the thickness of the shell elements is greater than 1/10 of the length or height, full integration is recommended.

How to Determine Whether Shell Elements are Thick or Thin:

The slenderness of shell elements is considered in terms of the characteristic length of the individual elements. The slenderness is defined as the thickness divided by the characteristic length. To determine the characteristic length and thickness:

- Use Tools

Measure and then click on two vertices to obtain the distance between them.

Measure and then click on two vertices to obtain the distance between them. - The thickness of the shell elements is defined within the General tab of the Element Definition dialog box.

- Alternatively, use Tools

Min/Max Length to determine the minimum and maximum length of the lines comprising the model. This is a global tool, so hide parts that you don't want to consider in your length inquiry.

Min/Max Length to determine the minimum and maximum length of the lines comprising the model. This is a global tool, so hide parts that you don't want to consider in your length inquiry.

Note: The General shell element formulation can be applied for both thick and thin shells. Also, you can refine the model by using the appropriate analysis formulation or the Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option. These settings are found within the Advanced tab of the Element Definition dialog box. Consider the following facts when choosing among the element formulations and options:

-

Slenderness > 1/10:

Thick shells are needed whenever the transverse shear stiffness is important (that is, when the consideration of transverse shear has a significant effect on the results). For homogenous, isotropic shell elements, transverse shear stiffness becomes important when the slenderness is more than about 1/10. Therefore, use General shells and do not activate the Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option in such cases.

-

Slenderness <= 1/10:

Thin shells are needed when transverse shear stiffness is minor or insignificant, and when the Kirchhoff constraint (see below) must be satisfied accurately. For homogeneous shells, this occurs when the slenderness is less than about 1/10. Therefore, you can specify Thin shells in such cases or use General shells but activate the Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option.

- The Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option is applicable to all nonlinear analyses using General shell elements [MES, Static Stress with Nonlinear Material Models, Natural Frequency (Modal) with Nonlinear Material Models, and MES Riks analyses].

- Shear locking may occur for General shells. If you use General shells for thin elements and experience shear locking, you may want to activate the Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option. Shear locking is characterized by a severely underestimated shear displacement. In the case of nonlinear modal analyses, this phenomenon can result in the calculation of excessively high natural frequencies.

- The shear locking phenomenon typically causes a reduced rate of convergence for coarse meshes, independent of any critical parameters (such as high-frequency oscillation or other types of instability in the structure). It is better to first address mesh quality or excessive coarseness issues and then to consider the Reduced integration for transverse shear terms option if the slenderness is still less than or equal to 1/10.

Kirchoff Constraint:

In thin shell theory, the element normal remains orthogonal to the shell reference surface (known as the Kirchoff constraint). This is graphically shown in the following image. The red line represents the element normal and the magenta lines are the edges of the midplane (reference surface):

Co-Rotational Shell Elements

In addition to General and Thin, the Co-rotational shell element formulation is also available. This formulation provides for robust solutions for composite and thermal material models. The Co-rotational shell element was formerly know as the "Enhanced" shell.

For Co-rotational shell elements, the Suppress drilling DOF check box can be activated to help models converge. This option cannot be used if a local coordinate system is being used in the model.

Basic Steps for Use of Shell Elements

- Be sure that a unit system is defined.

- Be sure that the model is using a nonlinear analysis type.

- Right-click the Element Type heading for the part that you want to be shell elements.

- Select the Shell command.

- Right-click the Element Definition heading.

- Select the Edit Element Definition command.

- In the General tab, select the appropriate material model in the Material Model drop-down box.

- Enter the Thickness of the shell elements. This is required information and the model will not run without it being entered.

- If the Composite or Temperature Dependent Composite option is selected in the Material Model drop-down box, specify the appropriate data in the Composite tab.

- Click the Orientation tab.

- Specify an element normal point. The top of the shell element will always point away from this point.

- Press the OK button.