Minor losses are the pressure losses attributed to the fluid flowing through fittings, valves, bends, elbows, tees, inlets, exits, enlargements and contractions.

In large networks with long pipes, pressure losses due to channel components are minor compared with frictional losses. In networks, such as cooling circuits in molds, that may have many bends, or elbows with partially throttled valves, then these minor losses may be the cause of the largest pressure loss in the system. Minor losses are determined experimentally, usually by the manufacturers of the component, and represented by a loss factor, K, on the component's data sheet. It is important that you use the actual manufacturer's empirical data for simulations rather than generic data, for more accurate results.

Empirical relations are used for branching flows and these are widely published. Refer to Idelchick6 and Miller7 for extensive studies on loss factors for components and branching flows.

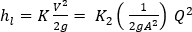

Mathematically, minor losses are accounted for through the resistance coefficient, or K factor. When the K factor for a component is readily available the pressure loss for the component can be represented as follows:

By looking at the Darcy-Weisbach equation:

it can be seen that the term

can be interchanged with the loss coefficient,

can be interchanged with the loss coefficient,

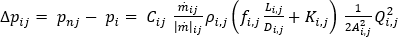

. This correlation suggests that the minor loss can be expressed as an equivalent length of the existing pipe or duct. Hence the discretized form of the Darcy-Weisbach equation can be written to include minor losses:

. This correlation suggests that the minor loss can be expressed as an equivalent length of the existing pipe or duct. Hence the discretized form of the Darcy-Weisbach equation can be written to include minor losses:

This equation represents the discretized form of the pressure loss equation that takes pipe friction and minor losses into account.