You control a joint's resistance to motion, and its tendency to return to its original position, by setting Ease, Damping, and Spring Back options.

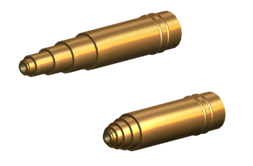

Moving telescopes with and without damping

Easing a Joint at Its Limits

An organic joint, or a worn mechanical joint, moves freely in the middle of its range of motion but moves less freely at the extremes of its range. Use Ease to cause a joint to resist motion as it approaches its From and To limits.

For example, your forearm might move freely in the middle of its range of motion, but it resists movement when you try to squeeze it against your upper arm or extend it all the way out. Ease simulates this effect.

Damping Joint Action

As a joint corrodes, dries out, or is put under a heavy load, it resists motion along its active axes. Damping simulates the natural effect of joint friction or inertia. Enter a value greater than zero in the Damping field to apply resistance over a joint's full range of motion.

As damping increases a joint resists motion and other joints are required to move more. A damping value of 1.0 means there is extreme resistance and a joint will not move on that axis.

For example, a telescope with no damping at all allows each cylinder to move to its maximum limit before the next cylinder moves. If the cylinders have damping values assigned, then each cylinder causes its parent to begin moving before it reaches full extension.

Setting a Joint to Spring Back

When a joint resists motion, it also has a tendency to return toward its at-rest position. You simulate this by setting Spring Back tension in the joints. As the joint moves further from its rest position, an increasingly larger force pulls the joint back, like a spring.

When you set Spring Tension higher, the spring pulls harder as the joint moves farther away from its rest position. Very high settings can turn the joint into a limit, because you can reach the point where the spring is too strong to allow the joint to move any farther.